I’ve come

to think of this stereotypical cloisonné dragon design as “Lao Tian Li’s”

because it is so distinctive and coincident with his lifetime [circa 1860-1930?]

I wondered

if it was the workshop where he was employed that set the standard for cloisonné

dragon iconography for at least 50 years.

I’m not saying Lao Tian Li invented the dragon iconography – here’s a

Chinese dragon design in brass:

And a much older Ming dragon in the British Museum:

However, the cheerful 20th century Chinese cloisonné

dragons are quite distinctive from the bristly Japanese or earlier Chinese

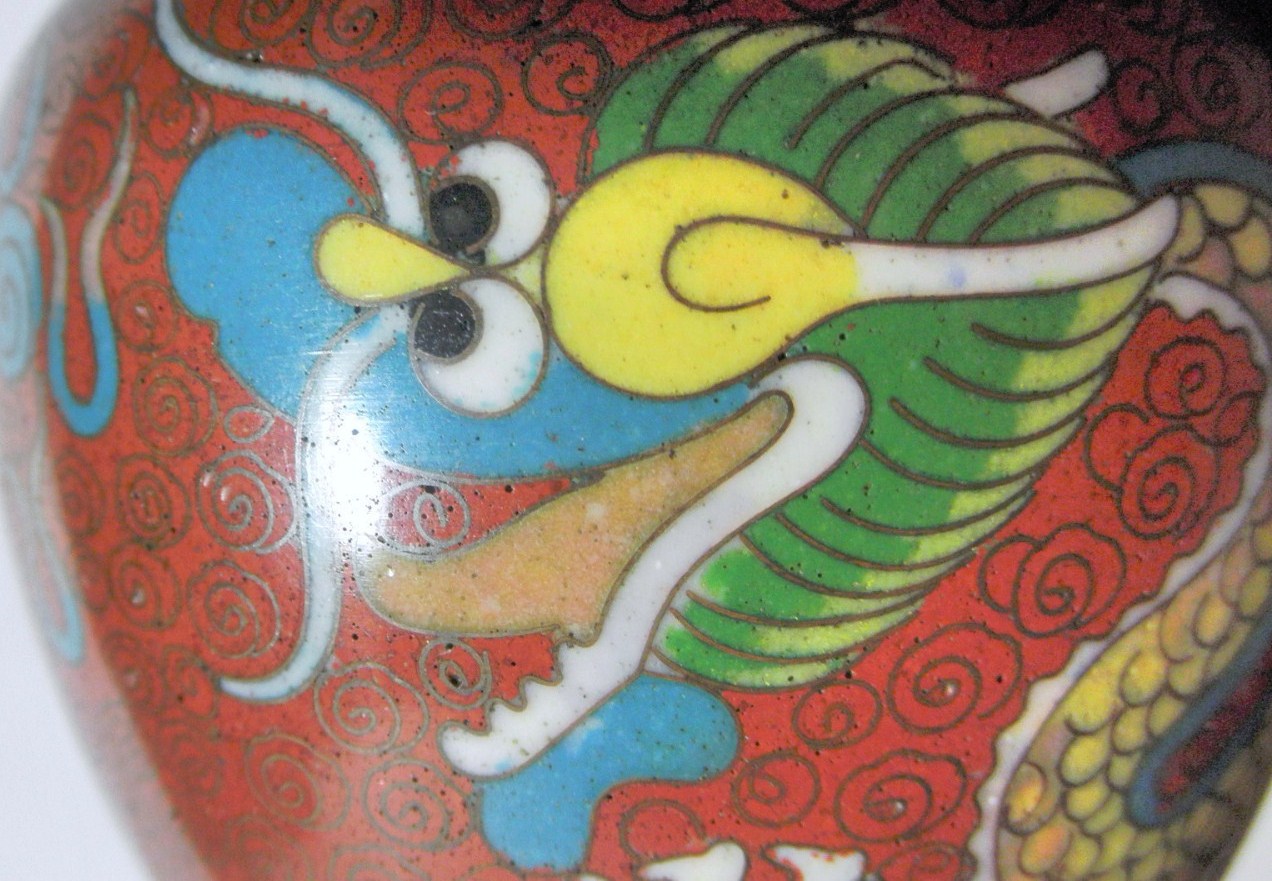

representations. Lao Tian Li’s signed

pieces are among the best versions, carefully detailed, showing a lively 5-toed

dragon with pointed claws and distinct toe pads and spurs on the legs, rounded chin

and distinctive bulbous snout with bumpy or spiky edges, a pair of sinuous barbels

alongside the nostrils, animated close-set black and white eyes, pronged horns emerging

from a bulbous dotted base on the dragon’s forehead, open mouth with curved

pointed tongue, angled jaw defined by a double line, fangs with outer pointed

tushes, and flowing mane. The body

scales are neatly applied, with individual scales following the belly edge

(instead of merely a wavy line) and a thin barbed crest along the back. Head, claws, tail and body are proportionate

to one another. Uniform small rounded crinkly

clouds with a tight round center fill the background and are very neatly and evenly applied.

Two variant poses are

common :

1) a long profile

suitable for the edges of boxes and shallow bowls or for curling around a vase

or candlestick;

2) a frontal rather geometric head-on view with a spotted

forehead, squared lower jaw, and “Comin’ atcha!” expression. This latter

frontal view seems to have been a favorite for having fun with variations in

colors and design details, although the overall layout remains

stereotypical.

The worst craftsmanship of all seems to appear on items

featuring a third rather awkward hybrid pose: the sprawled body with outspread

claws of the frontal pose combined with a sort of three-quarters profile

head.

In many versions of this hybrid Pose 3, basic artistic mistakes can be seen such as the awkward spots where the head overlaps the body, often seeming to sever it.

This pose seems to cluster in items made from the 1930s through the 1970s, and may have been the favorite of one particular artist or workshop. I haven’t been able to find examples that are unequivocally from earlier decades, and none at all signed by Lao Tian Li.

In many versions of this hybrid Pose 3, basic artistic mistakes can be seen such as the awkward spots where the head overlaps the body, often seeming to sever it.

This pose seems to cluster in items made from the 1930s through the 1970s, and may have been the favorite of one particular artist or workshop. I haven’t been able to find examples that are unequivocally from earlier decades, and none at all signed by Lao Tian Li.

Simplified versions of dragons in all three poses often look

bulb-nosed and cross-eyed, with a jelly bean chin.

Pre-World War 2 Chinese cloisonné production seems to have

been a combination of high quality pieces produced by urban workshops under a

master or masters, and a cottage industry in villages that produced folk-art

items to sell for cash to supplement their agricultural income. Once the basic dragon stereotype was set, it

was adhered to even in the more casually made household bric-a-brac. If one’s task is to work with standardized

pieces and a memorized pattern, turning out the same basic design over and

over, neatness and efficiency are probably of greater concern than personal

artistic expression. Nonetheless, even in small and presumably less expensive

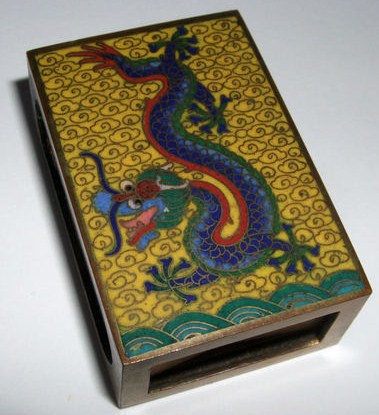

pieces such as matchboxes, a difference is obvious between pieces made by

someone with artistic ability who cared, and by someone who was just doing work.

It can be hazardous to try to date a piece

from the hodgepodge of painted, stamped, engraved, or papered labels that

might have been applied. I (and apparently many online auction sellers) have

difficulty sorting items into approximate age categories – Late Qing? Early

Republic? Roaring 20s? Depression 30s? Warring 40s? Nonetheless, production

does seem to get less detailed and meticulous around the 1930s, for entirely

understandable reasons – worldwide economic depression, wars, occupation, and

older Qing-era craftspeople fading from the scene. A crude four-toed dragon, often with black

eyes, seems to have appeared on beads and fashion accessories around the late

1930s. These beads show up in Japan as

well as in the United States - more on them in an upcoming post.

|

| A carefully worked cigarette case |

|

| My cute litte dragon box - the cloison wires are hair-thin. |

|

| Great little matchbox with good design, color, and workmanship |

|

| tA small inro-style purse of careless work. |

The JingFa cloisonné factory was founded in 1956. By this time the People’s Republic had been

through a terror and political purges, but Mao’s Famine and Cultural Revolution

were still to come. Collectivization of

the agricultural villages and famine likely reduced the population of part-time

cottage artisans. It’s difficult to see

how high quality cloisonné production could have persisted under such

circumstances, but apparently some artists and workshops struggled onward trying

to produce well made versions of traditional Chinese motifs, revolutionary

themes, and “modern” designs that might appeal to foreign buyers.

By the early 1970s arts and craft production was being

encouraged by the government in order to earn foreign exchange (Pier One

Imports and Lillian Vernon come to mind). The Montreal Gazette of Oct 2, 1973 recounts

how despite the ongoing Cultural Revolution the remaining older artisans had to

totter out of the back rooms and show the newer workers how to make the

old-style designs instead of revolutionary themes. The last gasp of the older dragon stereotype

seems to occur around the 1970s. Then it

appears that newer artistic directors took over in the factories and workshops

and instituted their own standard dragon patterns and motifs.

|

| Small bowl from c1930s on left, similar bowl from 1980s-90s on right. Note the difference in the style of clouds in the background - JingFa (Beijing Enamel Factory) post-1960 clouds on the right. |

|

| Vibrant modern covered jar from eBay seller liwz88 in Beijing |

No comments:

Post a Comment