Frequently encountered when trawling the Internet looking

for information on Chinese cloisonné ateliers such as DeCheng and Lao TianLi

are statements about awards won at the international exhibitions held in 1904

in St. Louis and 1915 in San Francisco; but, pictures of the actual pieces and

their award medals and certificates seem impossible to find. However, thanks to digital publishing,

historic records of these exhibitions can be searched to produce interesting

bits of information about who exhibited and what they exhibited, and how prizes

were awarded.

|

| History of the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition https://dl.mospace.umsystem.edu/mu/islandora/object/mu%3A334765#page/308/mode/2up |

China: Catalogue of the Collection of Chinese Exhibits at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St.Louis 1904 is one such resource. It

is available in an Internet Archive digital edition that is wonderfully easy to

use; the pages can be turned as if reading a book, or by using the slide bar at

the bottom, or searched via key words (I simply used the word “cloisonné” in

the search box). It contains much other

fascinating information about Chinese culture circa 1900 besides cloisonné, but

we’ll stick to the subject here.

Pages 54-56 [use the slide bar] list the “Modern Cloisonnes” that were exhibited

– an astonishing variety of objects from vases to umbrella handles.

Pages 56-57 contain a description of the process of

cloisonné manufacture. I found it interesting to contrast the techniques with

those used in contemporary cloisonné factories and workshops, and to note that

gilding with electroplating (“an ordinary

galvanic process”) was in use instead of - or perhaps as well as -mercury

gilding.

Also of note, for those interested in late Qing cloisonne, is this statement about the effort to produce quality work:

"The manufacture of cloisonne at Peking has revived during the past thirty years, and the Peking Industrial Institute is paying special attention to this art, which it hopes to bring up to the standards of the old enamels of the Ming dynasty and the period of the Emperor Ch'ien Lung."

Page 222 seems to contain a reference to the origin of openwork cloisonné (where the background

between the design elements is not filled in with enamel, giving a raised

effect that is often confused with champlevé).

The writer lists two items, a Qianlong vase and a DeCheng plate:

6. “Kien Lung" Cloisonné Vase. This perfect specimen

of the best Chinese Cloisonné of the “Tsing” Dynasty, 1736-1795, was among the

treasures of the “Yuan Ming Yuan” or Summer Palace in the early sixties. The

shape is very original, and all the coloring most harmonious.

7. Cloisonné Plate.

This specimen is in absolute contrast.

It is in the newest type of raised cloisonné, executed by the well known

firm of Te Cheng at Peking.

|

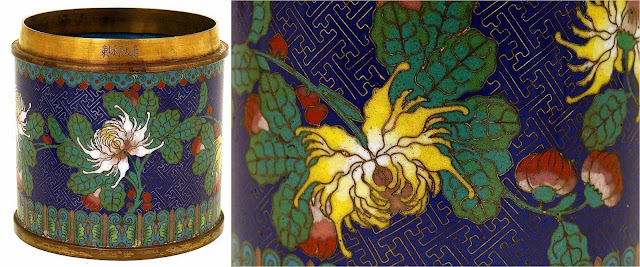

| Perhaps the "TeCheng" plate was similar to this piece? [which may or may not be a more recent production - readers, feel free to comment and express an opinion] |

|

| Readers might want to compare this plate with this one that features a DeCheng stamp and paper label. Is the lighter rectangle on the brass base evidence of a similar former label? |

|

| Observe how the lack of backqround enamel creates the appearance of champleve. |

Pages 333-334 list a variety of cloisonné objects “Exhibited

by Kwong Cheong Tai – Canton, Original Objects of Art Workmanship,” followed by

a few mentions of cloisonné table tops in furniture. Other cloisonne exhibitors are listed in various places (remember the keyword search function).

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The 5-volume history of the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibit in

San Francisco can be found at Internet Archive and Google Books:

The Story of the

Exposition: Being the official history of the international celebration held at

San Francisco in 1915 to commemorate the discovery of the Pacific Ocean and the

construction of the Panama Canal, by Frank Morton Todd.

Volume 1 at the Internet Archive features a photo of Chinese cloisonné in the Palace of Fine Arts on page 30, with accompanying text

description of the Chinese exhibit starting on the previous page.

Volume 3, page 287, chapter LIV, The Forbidden City, describes the Chinese effort at the exhibition.

In contrast to the 1904 St. Louis exhibition, by this time

China was no longer ruled by the Qing dynasty.

The author enthusiastically starts the chapter:

"Her entry into the

Panama-Pacific International Exposition was the first official revelation of

modern China to the modern world. At

previous expositions the Chinese exhibits have been made under the direction of

the Maritime Customs Administration, a bureau largely composed of foreign

officials which generally collected the material in the treaty ports and took

or sent it to the exhibit palaces. The

year 1915 saw the manifestation of a different spirit, a decision to

participate as a nation, on a basis of Chinese nationality. It was the first time China had so officially

participated in any exhibition outside her own borders, and she showed in her

pavilion and throughout the exhibit palaces a revolution in ideas and ideals –

the tremendous intellectual turnover of a vast empire."

The whole chapter is rather quaint reading. “The 56 models

of pagodas,” for example, likely refers to the awesome Tushanwan Pagodas.

Who exhibited? Starting on page 82, The Official Catalogue of the Palace of Fine Arts, Panama-PacificInternational Exposition, lists the cloisonne works in the Chinese section.

Cloisonné exhibitors

on the list are Pao Hua-leo, Teh Hsin-chen (De XingCheng), Teh Chang (De Cheng),

Yang Tien-Li, and Lao Tien-Li (Lao TianLi). What I understand to be

contemporary Pinyin renderings of three of the names are in parentheses. All sorts of mysterious things are

listed. Noticing item No. 71 for Teh

Hsin-chen, a “Dragon-handled Sprinkling Pot,” I wondered if it was something

such as these openwork ewers:

|

| An openwork ewer with DeCheng characters bottom stamp. |

|

| The site featuring this ewer also cites a similar dragon ewer, no. 140, in Beatrice Quette's book, Cloisonne: Chinese enamels of the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties. |

The flyer described in the post on DeXingCheng states that

the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915 was one of the exhibitions

in which the firm was awarded gold and silver medals together with diplomas.

I wondered why, in the Panama-Pacific list of exhibitors, awards are listed in italics under the names

in many other categories - such as porcelain, lacquer, stone, and glass - but

none in the cloisonné section?

Volume 4, of Frank Morton Todd’s account, beginning on page369, Chapter LXIX, The High Court of the Arts describes the jury system for

awarding the medals.

"These juries were

composed of men of renown; such authorities and masters of craft as … C. Y. Yen

of China in the field of the Fine Arts;"

Mr. Yen appears in the

group photo of the Superior Jury, the decision-making group for the awards.

Wading through the complete chapter is a bit of a slog, as

it goes into detail about how the juries were selected and points awarded, as

well as the levels of awards – bronze, silver, gold, and the highest, the medal

of honor. Grand Prizes were the best

exhibits in their class. Diplomas of honorable mention were also awarded,

without a medal. The author states,

“There

were 25,527 awards, involving the issue of 20,344 medals and 25,527 diplomas.” And, “The

work of issuing the diplomas and medals occupied the Secretary of the Award

System and six assistants for more than two years after the close of the

Exposition.”

So the Chinese cloisonné medals from the 1915 San Francisco

exhibition remain a bit of a puzzle.

Susan’s Weber’s chapter in Beatrice Quette’s Cloisonné: Chinese enamels from the Yuan,Ming and Qing Dynasties is an impressively researched piece on how the

great public exhibitions of the late 19th and early 20th

centuries inspired collectors worldwide – wealthy connoisseurs, public museums,

humble department store shoppers - to develop a taste for Chinese

cloisonné. Weber’s selection of photos

is superb. She covers not only

collectors in Britain, France, and the United States, but Germany, Hungary, and

Russia as well. It’s an awesome piece of

documentation – 33 difficult-to-find pictures, 6 pages of bibliographic citations at the

end. Above examples of original

publications give some idea of the type of research swamp Weber had to wade

through to assemble her article, providing yet another reason for anyone

interested in Chinese cloisonné to rush out and get a copy of Quette’s book.

A glimpse of what these exhibitions were like can be seen in

the quaint stereoviews collected at The Hillman Stereo Archive.

UPDATE: An example of the mix of information about Lao TianLi's pieces exhibited in 1904 and 1915 can be seen in this Chinese site, featuring a pair of vases with a Lao TianLi export style base stamp, and a reference to a "Baoding stove" 宝鼎炉 - Google Translate's phrase for the name of an impressive incense burner. The author of the auction listing says,

In 1904, Lee made God "Baoding stove" won the first prize at the Chicago World's Fair in 1915 and re-award the Panama Pacific International Exposition. Heaven Lee facility is located Po Temple Street, foreign built, and more products for export, are printed on the base "God benefit system" Ming paragraph.

The 1904 exposition was in St. Louis, not Chicago. The Qing government did not officially participate in the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, although wealthy Chicago Chinese did organize exhibits. You can read some very interesting accounts of the Chicago fair at the Chinese-American Museum of Chicago website.

Doing a Google search for 宝鼎炉 resulted in this image:

A Chinese article in which it appears states [translation by Google]:

"In 1904, St. Louis, the fourth largest city in the United States, held the World's Fair to celebrate the glorious history of the purchase of Louisiana from Napoleon for $15 million 100 years ago. Therefore, the St. Louis Expo USA also invested 15 million US dollars. This World Expo is the fourth year that the Eight-Power Allied Forces invaded China. The Qing government, with its country wide open, finally led a business delegation to participate in the World Expo in an official form for the first time.

In 1904, Lee made God "Baoding stove" won the first prize at the Chicago World's Fair in 1915 and re-award the Panama Pacific International Exposition. Heaven Lee facility is located Po Temple Street, foreign built, and more products for export, are printed on the base "God benefit system" Ming paragraph.

The 1904 exposition was in St. Louis, not Chicago. The Qing government did not officially participate in the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, although wealthy Chicago Chinese did organize exhibits. You can read some very interesting accounts of the Chicago fair at the Chinese-American Museum of Chicago website.

Doing a Google search for 宝鼎炉 resulted in this image:

A Chinese article in which it appears states [translation by Google]:

"In 1904, St. Louis, the fourth largest city in the United States, held the World's Fair to celebrate the glorious history of the purchase of Louisiana from Napoleon for $15 million 100 years ago. Therefore, the St. Louis Expo USA also invested 15 million US dollars. This World Expo is the fourth year that the Eight-Power Allied Forces invaded China. The Qing government, with its country wide open, finally led a business delegation to participate in the World Expo in an official form for the first time.

Laotianli, an enamel workshop from Beijing, brought its own "Baoding Furnace" to the exhibition and won the first prize. Laotianli was the most famous cloisonne workshop at that time, and it was also an early foreign-funded enterprise, and most of its products were exported. This is the first time that Chinese cloisonne craftsmanship won the World Expo. In the 1915 San Francisco World Expo, cloisonne won the first prize again."

"Appreciation of Laotianli Baoding Furnace"

While the booklet for the 1904 St. Louis exhibition (China: Catalogue of the Collection of Chinese Exhibits at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St.Louis 1904 ) does list large incense burners among the cloisonne objects displayed, there is no information about who made them or from what workshop they originated. The listing for the 1915 San Francisco Panama-Pacific exhibition quoted above does not include an incense burner under the works by Lao TianLi, only "Rich Colored Vase" and what I am guessing are tripod portrait frames.

"Appreciation of Laotianli Baoding Furnace"

While the booklet for the 1904 St. Louis exhibition (China: Catalogue of the Collection of Chinese Exhibits at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St.Louis 1904 ) does list large incense burners among the cloisonne objects displayed, there is no information about who made them or from what workshop they originated. The listing for the 1915 San Francisco Panama-Pacific exhibition quoted above does not include an incense burner under the works by Lao TianLi, only "Rich Colored Vase" and what I am guessing are tripod portrait frames.

What is the actual source for this photo? Is it a piece now held in the Palace Museum? Does anyone know?

UPDATE: Zheng Yiwei, in his discussion of three censers pictured in Figure 27 of his book, concludes that the censer pictured above is a copy of a censer listed in 1985 as a work by Jin Shiquan (a master artist at the Beijing Enamel Factory), contrasting it with a censer at the Brooklyn Museum that was acquired early in the 20th century.

|

| Brooklyn Museum censer, 1909 gift of Samuel P. Avery |

|

| The Brooklyn Museum censer. The museum attributes it to the Qianlong era, but note the openwork in the legs and finial. This style of cloisonne is attributed to "Te Cheng": in the 1904 publication about the St. Louis Exhibition: "It is in the newest type of raised cloisonné, executed by the well known firm of Te Cheng at Peking." A very similar censer pictured in Fig. 74 of the Neglinskaya book on cloisonne is attributed to late-19th early 20th century. Brooklyn Museum link, with good closeup photos |

|

| Neglinskaya book |

|

| Brooklyn Museum censer on left, Jin Shiquan censer in middle, censer on right Zheng Yiwei believes to be a copy of the Jin Shiquan work, not a censer by Lao Tianli |

官方授权卖家: CNCE.

《景泰蓝的海外贸易:晚清到共和国百年商史》(郑轶伟)

A Centennial History of Chinese Export Cloisonne From Late Qing To The People's Republic of China

作者:郑轶伟

出版社:上海文化出版社

ISBN:9787553519555

装订方式:平装

版次:第1版