At least half a dozen names appear in various c.1900 publications such as guide books, auction catalogs and exhibitor lists - Yang tien-li 楊天利, for example. Zhang Rong, in her chapter in Beatrice Quette's book Cloisonne: Chinese Enamels from the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, mentions Laotianli 老天利, Jingyuantang 静远堂, Zhiyuantang 志远堂, Baohuasheng 寶華生, Dexingcheng 德興成, and Decheng 德成.

What clues might tell these workshops apart? Do stylistic variations perhaps trace the career of particular artists, such as Laotianli, from when they started out as a young artists in someone else's shop to when they founded their own ateliers?

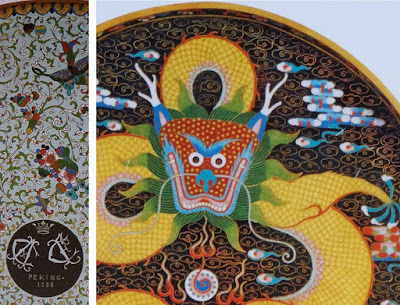

A particularly interesting plate is described in M. Neglinskaya's book. It features the actual signatures, exactly copied in cloisonne wires, of four Russian diplomats, wealthy merchants or bankers, and a medallion with the Cyrillic initials CE and CA and "Peking 1888." The initials are believed to refer to the Startseva (Elders) family, perhaps Alex Elders and his daughter Elizabeth. The cloisonne workmanship is superb.

Also featured in the Neglinskaya book is a large circular cloisonne tray with a dramatic dragon in frontal pose.

|

| Peking 1888 plate and dragon tray from Neglinskaya |

A large plate from an online auction a few years ago features a dragon and decorative border similar to the two pieces in the Neglinskaya book. The likelihood of the border design being the work of two different artists is remote, thus it seems reasonable that the plate may also date from around 1888.

|

| It is extremely doubtful that this exact border could be the design of two different artists. |

Comparing the dragon plate to the Neglinskaya tray, we observe a difference between the curled and spiky whiskers surrounding the lips, but otherwise the dragons are strikingly similar:

Two large 10" bowls display a dragon very similar to that in the plate, although with a ruyi border instead of the border of tiny leaf pairs:

|

| The seller stated: "It is 26 cm or 10" diameter and is 2.75" tall. It dates c 1900-1910. It was from a Cheshire estate sale of a large collection of Oriental antiques and art." |

|

| Dragon in second bowl compared to first |

|

| Plate, Neglinskaya tray, and 10" bowl. Note that the tray is a photo of a photo in the book, so color reproduction may not be accurate. |

Two other bowls similar to the 10" examples:

An 8" pedestal dish, or tazza, featuring a similar dragon with spiky whiskers:

|

| Plate with tightly curled whiskers, pedestal dish with spiky blue flame-like whiskers. |

A comparison of all the dragons listed above:

|

| Opening the picture in a new tab, then clicking on the "magnify" button will allow closer inspection of details. |

And for further comparison, dragon designs on works with engraved LaoTianLi signatures:

|

| Large plates |

How to sort through all this puzzling evidence? The Dexingcheng atelier claimed to have been established around 1860, Yangtienli in 1874.

Did Laotianli learn this distinctive style of dragon from working in shops like these? What other workshops continued to use this dragon design, perhaps into the 1930s?

|

| Internet Archive copy of Thomas Cook travel guide, Peking and the Overland Route, 1917. |

Did Laotianli learn this distinctive style of dragon from working in shops like these? What other workshops continued to use this dragon design, perhaps into the 1930s?